Review: 5 stars

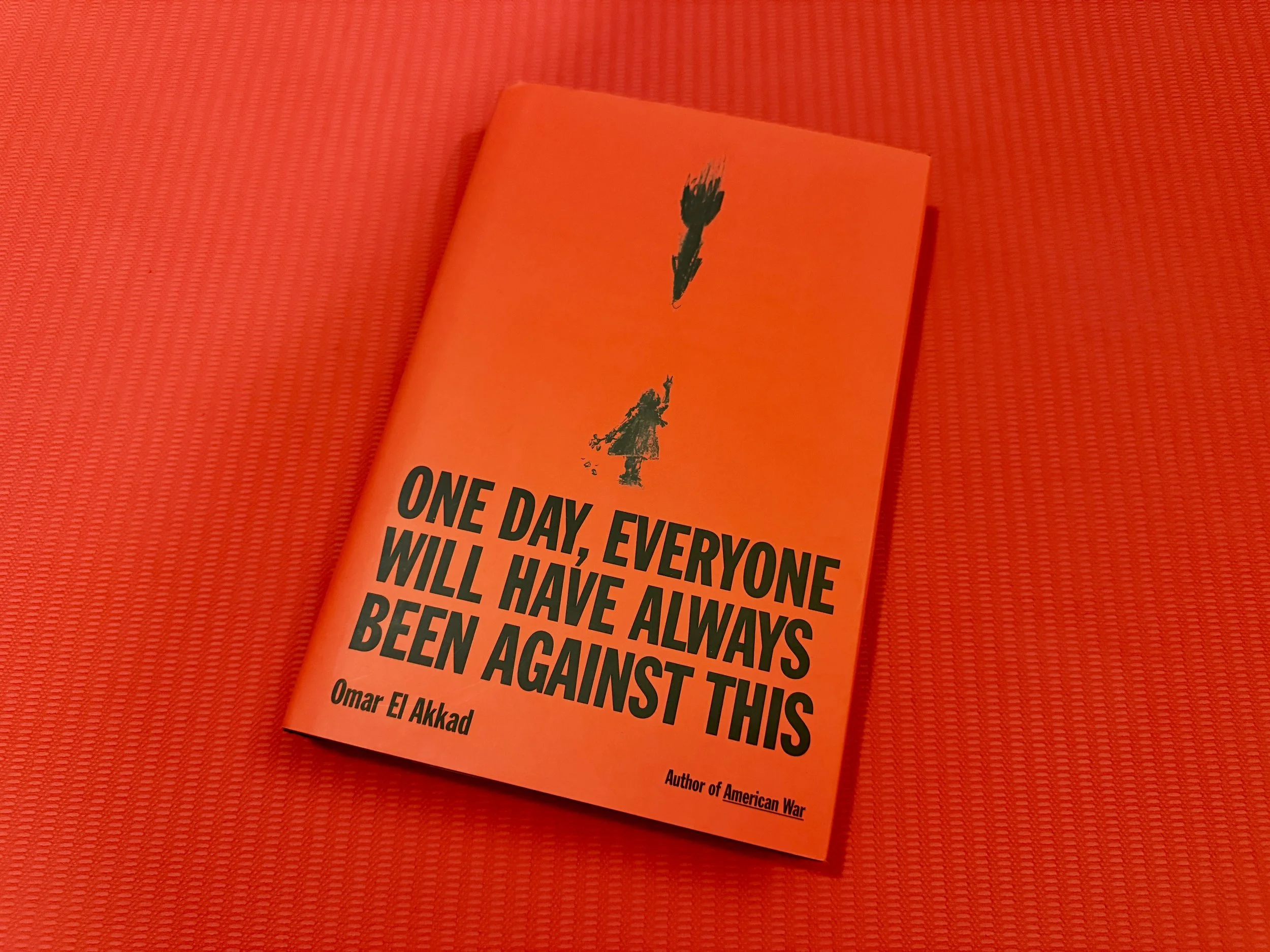

Omar El Akkad’s latest non-fiction book examines power, violence, and the language used to describe them, with significant attention to Gaza. Drawing on journalism, history, and personal reflection, the book considers what responsibility remains for those who witness events from a distance.

In particular, when the author takes a more journalistic and rhetorical lens on the genocide in Gaza, he makes a poignant point about the truths of the violence that occurred and who the victims were. What is undebatable is that lives were snatched too early, rendered collateral damage in the ongoing theatre of revenge. “When the past is past, the dead will be found to not have partaken in their own killing. The children will not have pulled their own limbs out and strewn them all over the makeshift soccer pitch.”

El Akkad fixates at length on the role of language in covering this conflict—the contortions Western media goes through to avoid blame, to preserve a veneer of objectivity, while failing what he argues is journalism’s moral mandate: to report facts. “Accidentally, a stray bullet found its way into the van ahead, and that killed a three- or four-year-old young lady,”reported by a British newscaster, is a sobering example of how traditional media cannot bring itself to speak forthrightly about a toddler being murdered at a military checkpoint.

I do not come to this book as an expert. My understanding of Israel–Palestine largely stops at high school history, and I would not claim intimacy with the full scope of events since October 7, 2023. What unsettled me most about El Akkad’s writing was not simply what I learned, but what it revealed about the narrowness of the viewpoints I tend to encounter. I am often spoon-fed stories from Facebook, YouTube, and other social media algorithms that quietly reinforce what I already believe - or think I know.. When I linger too long on a video or a post, those moments are already reshaping what my scrolling will reveal next, and I often find myself snapping back to what is safe, known, and accepted.

In the true spirit of setting New Year’s resolutions, I found myself wondering what El Akkad’s call to action might be in the face of such pain. His concept of “negative resistance” was particularly compelling—almost a foot-in-the-door path for bystanders who want to do more but are scared to start. He defines it as “refusing to participate when the act of participation falls below one’s moral threshold,” including seemingly small acts such as changing which businesses we consume from or refusing to attend certain events. It struck me as a practice many people with strong moral compasses already exercise: the deliberate introduction of friction into one’s life, a willingness to inconvenience oneself in the service of something larger.

I am grateful that I read this book as my first of 2026. It was an abrupt reminder to question what I see and hear, and to intentionally seek out divergent perspectives in order to understand any situation more honestly. I exercise this instinct readily in my professional life, but my capacity for active curiosity in my personal life has likely atrophied. In its place, another muscle has likely grown stronger: indifference. Perhaps this is true for many of us, conditioned by COVID, by constant crisis, by the daily shocks of modern news. As El Akkad writes, “No atrocity is too great to shrug away now, the muscles of indifference having been sufficiently conditioned.” This book does not allow us to shrug.